This is Part 2 of a 3 part series. Click here to read Part 1.

During the 2023-2024 school year, our son Luke, who is autistic and non-verbal, was abused by an assistant in his special education classroom at Central Elementary School, which is part of the Graves County School District in Kentucky. We later learned that the incident was never reported to DCBS (Child Protective Services). You can read about that here. During that same school year, Luke was also denied a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), guaranteed to him under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). In order to explain what happened to Luke, I need to provide you with some background. It’s a lot more technical than the first post, but just as important, especially for special needs parents.

What is FAPE?

The IDEA defines a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) as special education and related services that are

- provided at public expense;

- meet the standards of the state educational agency (SEA);

- include an appropriate preschool, elementary, or secondary education;

- are provided in conformity with the individualized education program (IEP).

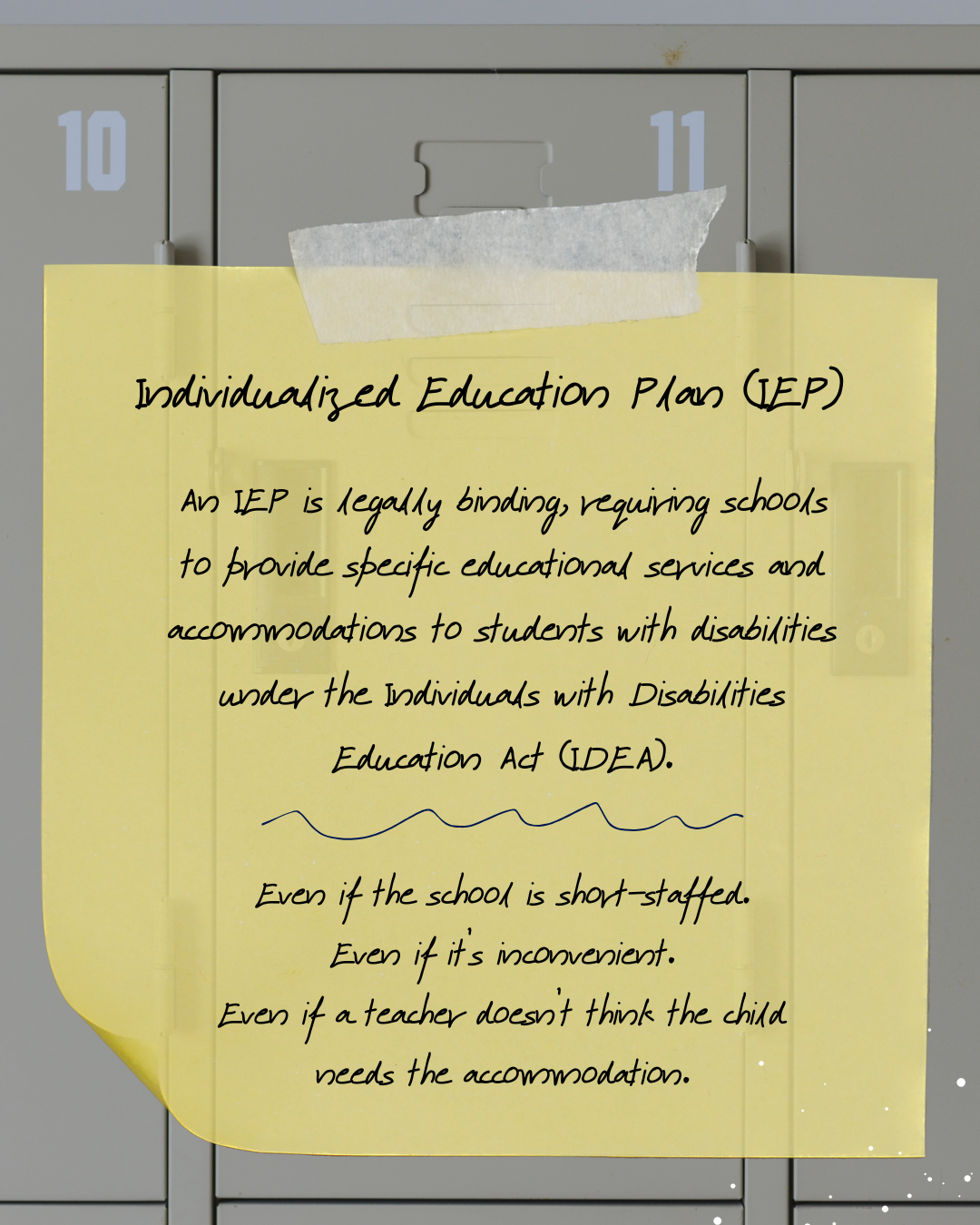

What is an IEP?

An Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is a legally binding document that serves as a contract between the parents and the school, mandating that the school provide the services and accommodations that are outlined and agreed upon in the document. It’s not a suggestion. It’s not optional. It’s federal law.

The IEP details the child’s present learning, annual educational goals, what special education services the child will receive, who will provide those services, and for how much time each week. It also outlines the accommodations they will receive and determines the child’s Least Restrictive Environment (LRE). A child’s LRE depends on the severity of their disability, support needs and their educational goals.

Denial of FAPE

Denial of FAPE happens when a school does not provide a student with a disability with the appropriate services, supports, and accommodations they are entitled to under the IDEA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. Examples include failing to provide special education services, related services or modifications that were included in a student’s IEP, providing fewer hours of services that were included in a student’s IEP, delaying the implementation of an IEP and failing to monitor progress on an IEP.

If a school district is found to be out of compliance, they could face potential consequences ranging anywhere from required compensatory services for the student or reimbursement for parental expense, to administrative action by the U.S. Department of Education including loss of federal funding.

Failure to Adhere to the LRE

The Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) allows for students with disabilities to be educated with non-disabled peers to the maximum extent appropriate. According to Luke’s IEP, he was supposed to receive “all core academic instruction in the special education classroom” but was still supposed to be around his non-disabled peers throughout the day. “Luke will participate in breakfast, lunch, recess, specials, and other social activities with his peers in the general education classroom as behavior and sensory processing allows.”

The clause “as behavior and sensory processing allows” seemed reasonable on the surface, but would prove to be the justification his teacher used for rarely allowing Luke to leave the special education classroom at all. (If this clause appears on your child’s IEP, have it removed immediately.) It was through several conversations with his special ed teacher Justin Cunningham, the class assistants, staff members and my personal observation from working at the school over several months that I learned:

- Luke was not taken to breakfast or lunch with his peers during his first grade year at all.

- Luke was not taken to specials with his peers during his first grade year at all.

- Luke went to recess sporadically through mid October, then not again for the remainder of the year until we withdrew him in February.

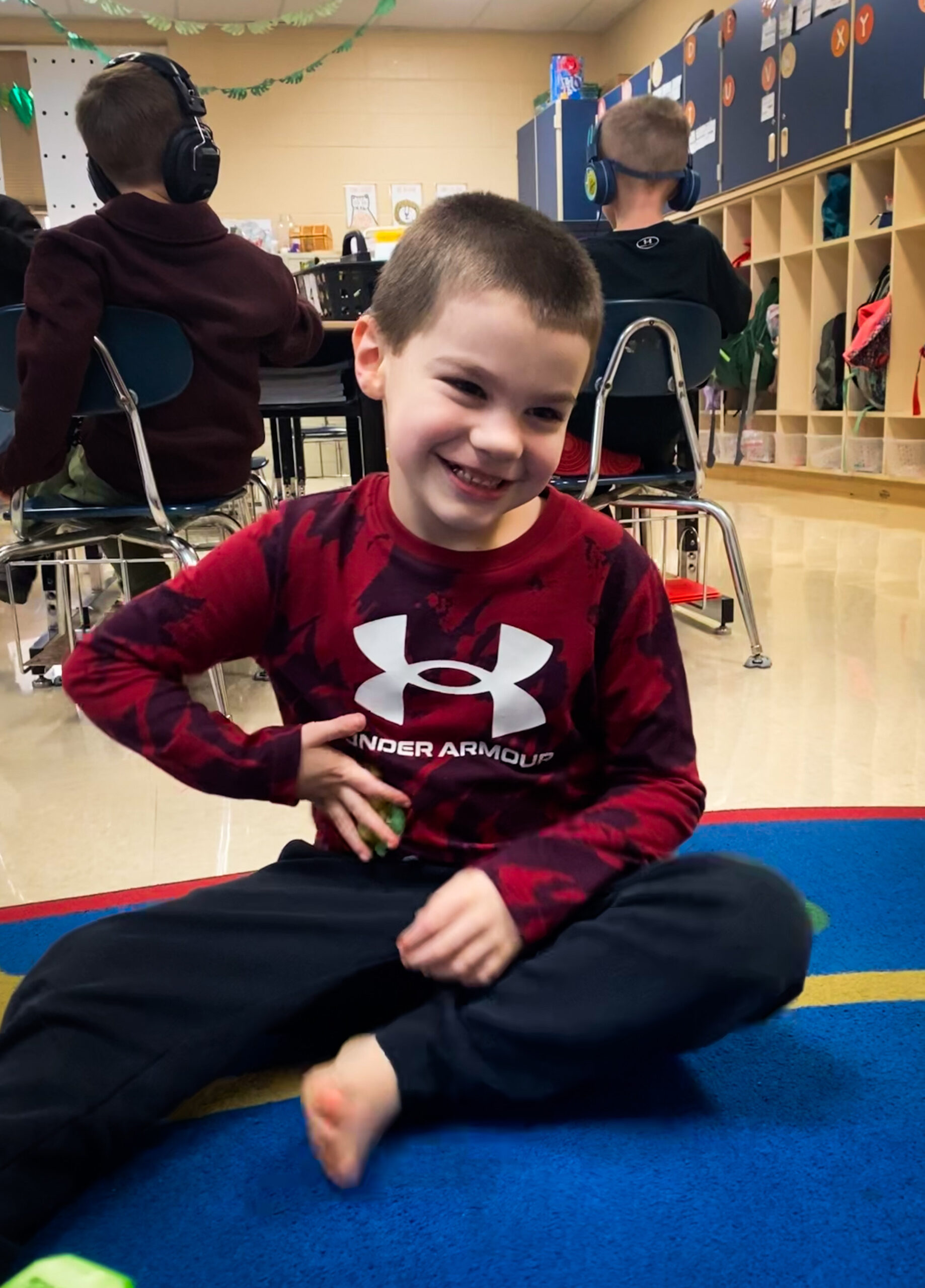

- Luke’s first time visiting his regular classroom was mid November, three months into the school year. For a few weeks, he was taken everyday and loved it. His classmates and his teacher loved having him there too. After Christmas break, he was taken to his regular class 3 times in January then not again, despite requesting to go almost daily on his AAC device.

Instead of going to all of the places outlined in his IEP, Luke was confined to the special education classroom for the majority of the year, leaving only for speech, occupational therapy and the occasional trip to the sensory room.

Trapped in a room

I try to imagine what it would feel like as Luke to spend all day in a dimly lit room with no consistent schedule, watching classmates leave and come back while he stayed in the room, not knowing if or when he would venture out. I think about not being able to say “hey I’m bored” or “what am I going to be doing today?” or “I’m really overstimulated, I need a break”. I think about how it felt watching the kids from the window, eating lunch at the tables outside and not being able to say “I want to go outside”. I think about him being under so much stress that he stopped eating during the day and started sleeping for hours during school.

I think about the times he did request going places on his AAC device like the sensory room or his first grade class, only to be told “no” and handed a tablet. I think about how overstimulated his little nervous system was with all of that screen time. And then I think about how confusing it was for him when he used the only communication tool he had, his body, to communicate that he was overstimulated, frustrated, overwhelmed, tired or upset, only to get in trouble for pinching and then labeled the problem child.

I think about how anxious he must have been all those weeks he arrived at school to a different substitute teacher in his class everyday. Coming to school and never knowing what to expect would be hard on a neurotypical child, let alone an autistic one.

I think about how I asked everyday how Luke’s day went and was told “he had a good day!” or “We had an incident this morning but then he was fine”, only to learn later that the truth was being withheld from me, and an entirely different story was being shared with other staff members and parents.

Interruptions in Services

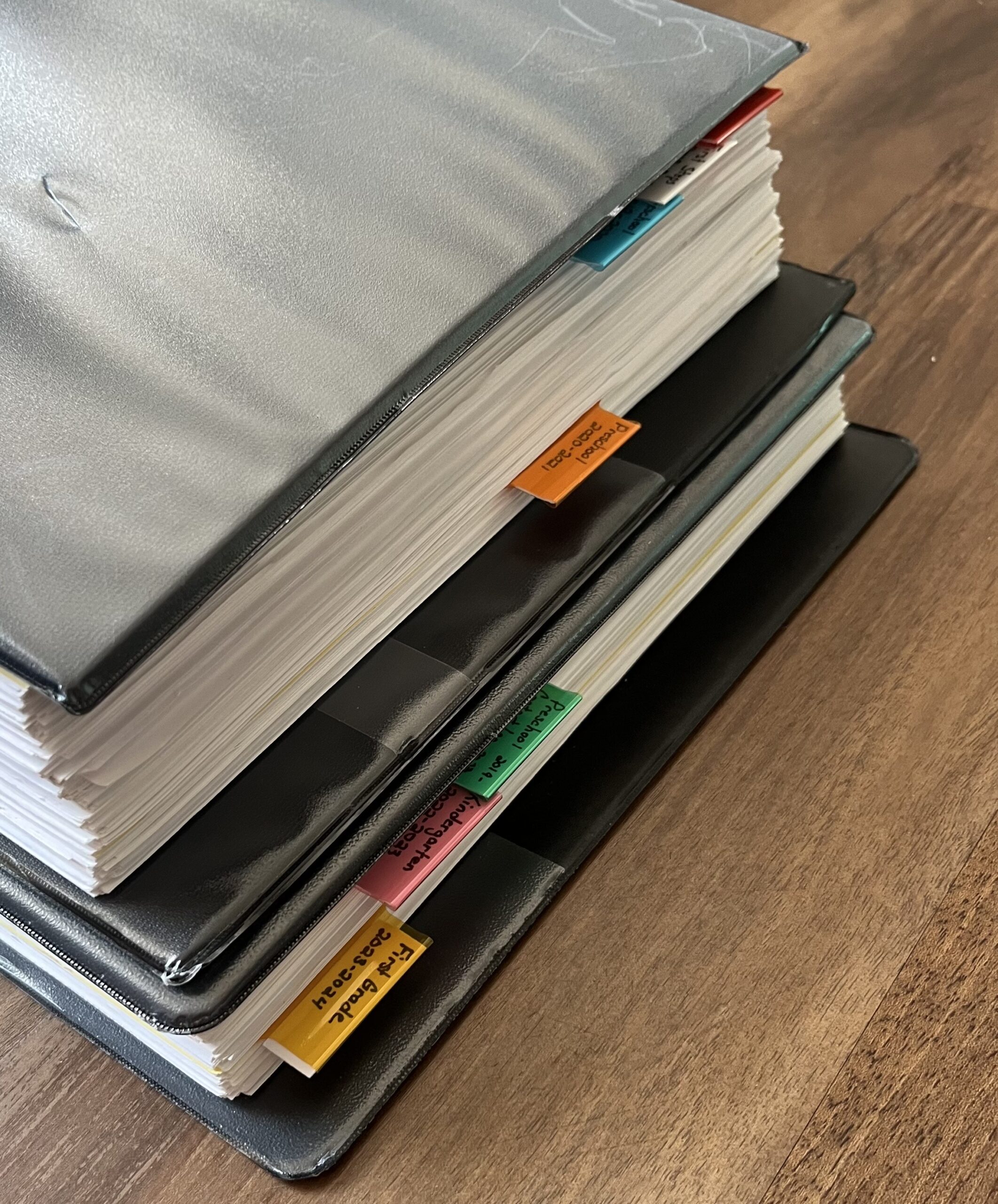

Every child’s IEP lists the services the child will receive, the person responsible for providing the service, and the amount of time spent each week. You can see Luke’s special education services from his 2023-2024 IEP here. Luke’s teacher missed weeks of school during the school year which caused a loss of progress and educational benefit for every student in the class. If a teacher has missed a significant number of days, the district is obligated to provide compensatory education. Compensatory education serves as a remedy when a school district has failed to provide a student with FAPE, aiming to make up for the lost instructional time and allow the student to catch back up to where they should have been.

A conservative estimate of lost instructional time, just for Luke, was 67.5 hours. No compensatory education was provided or offered by the Graves County School District.

No Evidence of Progress Monitoring

Nearly a month after withdrawing Luke from Central Elementary, we received copies of his student records and were shocked by what was missing. There were no progress reports on Luke’s annual goals that Cunningham was responsible for, no notes, and no other data related to Luke’s IEP goals from the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 school years when Luke was in Cunningham’s class. None.

Every nine weeks at report card time, I was supposed to receive a progress report that detailed Luke’s progress toward the goals outlined in his IEP. I would receive one from Luke’s speech teacher, but not Cunningham. He would say things like “I’m just about done with Luke’s progress report, I’ll put it in his backpack tomorrow.” Or “I’ve got it back in my room, I’ll get it to you later.” One time I asked to see the progress report and he said “well I can just tell you” and proceeded to verbally go through Luke’s progress. It didn’t seem like a big deal at the time. I figured I could always request Luke’s records and find the progress reports in there if I needed them. (If your child’s teacher is telling you these same things, learn from my mistake. Insist on getting a copy of your child’s progress notes every grading period.)

This was not a first year special ed teacher mistake. Justin Cunningham was a seasoned educator working on his doctorate. He was very knowledgeable about special education laws, procedures and best practices. He was trusted and respected by the special ed team. When we started noticing Luke becoming aggressive and pinching more at home, I went to him for advice. It was jarring to learn that the person I thought I knew wasn’t that person at all.

Without progress monitoring data and reports, I have no evidence that Cunningham worked on any of Luke’s IEP goals. All of those progress reports he said were completed didn’t exist. When I started homeschooling, the only document I had to work from was his IEP from the beginning of the year. We had to start from scratch.

None of this came together easily. The abuse, learning that Luke was not receiving the education he was entitled to, none of it. It took piecing together bits of information from a lot of sources over time to figure out what was actually happening to Luke. Searching for the truth is what ended up getting me fired, which I detail in Part 3.

Read the rest of the series here:

Luke’s Story: Speaking Up for Those Who Can’t–Part 1 (Abuse)

Luke’s Story: Speaking Up for Those Who Can’t–Part 3 (Improper seclusion and my termination)